Dozens of Dreamers ignored Vice President Joe Biden’s warning against public displays during the Senate’s historic vote on immigration reform, chanting, “Yes, we can!” But the bipartisan vote presided by Biden and the enthusiasm of dozens of Latino youths who packed the Senate gallery that day were celebrating a momentary victory that ignored the huge problems immigration reform continues to face.

What June’s Senate vote did was usher in phase two of the struggle for immigration reform as the issue moves to the GOP-controlled House for consideration. Some say the movement will die there. But most advocates aren’t giving up.

“I remain hopeful,” said former Clinton administration official Mickey Ibarra. “The consequences are so important to the Latino community and to the country.”

But Ibarra, president and founder of Washington D.C. consulting agency Ibarra Strategies, said he remains “very concerned” about the fate of immigration reform. He has good reason – GOP House leaders including Speaker John Boehner say the Senate bill is “dead on arrival.”

The massive bill approved by the Senate would make about 11 million undocumented immigrants eligible for legal status and put them on a 13-year path to citizenship. The bill would also spend billions of dollars ramping up security along the Rio Grande and toughening sanctions on employers who hire undocumented workers.Those tough enforcement measures are hailed by House Republicans. But they say the legalization of millions of undocumented immigrants, and the chance for eventual citizenship, amounts to amnesty, something they and their conservative constituents fiercely oppose.

Under attack by the right wing of his party, Boehner has said repeatedly he will never put an immigration bill on the floor that a majority of House Republicans don’t support, following the so-called Hastert Rule. After a meeting of the Republican conference on July 10, Boehner signalled that the House would take a piecemeal approach and introduce its own legislation.

So there’s no clear path in the House for sweeping immigration reform and a real possibility the effort will die again this year. Advocates like lbarra are hoping Boehner changes his mind and allows something similar to the Senate bill to have a House vote. That could happen in the fall, after the August recess. And if Boehner does allow a vote on comprehensive reform, there’s a good chance it would be approved with a majority of Democratic votes and a minority of Republican votes.

Laura Vazquez, immigration legislative analyst for the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), said she hoped the Senate’s decisive vote on immigration reform “will send a strong message to the House.” But there’s debate over how strong that message really was.

While the Senate vote for an immigration overhaul was 68-32, only 14 of 45 Republican senators voted for it. And Democrats had to cede a lot of ground to get those GOP votes. The biggest giveback was the approval of billions of dollars to what some call the “militarization” of the U.S. border with Mexico. That included the hiring of nearly 20,000 additional Border Patrol Officers and the purchase of new unmanned aerial vehicles, radar systems and dozens of helicopters. It also includes the construction of an additional 350 miles of fencing along the Rio Grande, a fully implemented exit and entrance visa program and a fully deployed E-Verify system that allows employers to check the status of workers.

“These elements are all elements Republicans have pushed for for years,” Corker said,” said Sen. Bob Corker (R-Tenn.), a main sponsor of the border provisions.

The bill also requires immigrants to pay a $500 fee to apply for legal status and pay any back taxes owed. Ibarra said those obstacles will be a deal killer for millions of immigrants. “How many people are going to say ‘Hey, I owe you this amount of taxes?’” he said. “And the application fee alone is going to turn a lot of people away.”

Then there’s the 13-year wait for citizenship. Ibarra estimates fewer than half of the nation’s 11 million undocumented immigrants would ever become permanent residents and even fewer would become citizens if the Senate bill becomes law.

The Senate bill was sold as “tough but fair.”

But some Latino advocates say it’s too tough. Rep. Filemon Vela, a freshman Democrat representing a South Texas district, quit the Congressional Hispanic Caucus over its severe approach to border security. “Erecting more border fence would chill the robust economic relationship that our country and our states enjoy with (Mexico),” Vela said.

Rep. Raul Grijalva (D-Ariz.), said there are other fissures in the caucus that have not come to light, but are likely to do so as the immigration debate heats up in the House in the fall. “There’s a lot to swallow in what the Senate approved, and it’s now likely anything the House considers will be better,” he said.

On the other hand, Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D-Ill.), has exhibited an almost unnatural optimism about Congress’ chances to approve immigration reform.“We’re going to find a way,” he said.

Most national Hispanic groups are supportive of the Senate bill. But increasingly, they are having reservations and are very nervous about what lies ahead. More than 30 Hispanic groups and civil rights organizations, including NCLR, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) and the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) are part of a coalition called Latinos United for Immigration Reform.

“This is the year for immigration reform,” said Hector Sanchez, chair of the National Hispanic Leadership Agenda.

But other Latino groups don’t think so. Presente.org and Border Network for Human Rights say no bill is better than what the Senate approved because its heavy clamp-down on the border would result in more crossing deaths. Ibarra said it will be increasingly difficult to hold the community together. “More and more, some are asking “Why should we support this?’” he said.

Despite some misgivings, most Latino groups, like NCLR, are working largely below radar, drumming up enthusiasm for the Senate bill among their members and quietly lobbying members of Congress. Ibarra said the White House, which is committed to comprehensive reform, advised the Latino groups to keep a low profile, and they agreed. “The Hispanic organizations are concerned about agitating and reducing the compromise. It’s a real tightrope,” he said.

Grijalva said he heard rumors that theWhite House told Latino groups to keep a low profile, “but I couldn’t confirm it. It makes sense that isn’t seen as just a Latino thing.”

The NCLR’s Vasquez replies that there was no such directive from Obama.“We’re very visible,” she said, noting that top NCLR officials have been invited to the White House to discuss the issue. Yet, the NCLR and the other groups that make up Latinos United for Immigration Reform are not running any ads, and Vasquez said she did not know of any plans to do so.

Meanwhile, several groups are running ads promoting reform, trying to give GOP lawmakers like Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida and Kelly Ayotte of New Hampshire some cover for their support of the Senate bill [see Strange Bedfellows, below]. Big business has always promoted immigration reform, even more so now since the immigration bill would make it easier for companies to hire foreign high-tech workers. Some Republicans are also embracing reform because they are concerned Latinos, a fast growing electorate, are turning away from the GOP and will deny the party any chance of recapturing the White House.

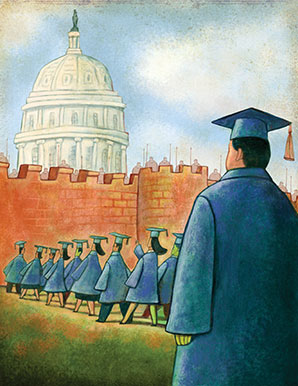

One Latino group that is not keeping a low profile is United We Dream, an organization formed 10 years ago by immigrant youths whose undocumented status kept them from paying in-state tuition at most colleges or applying for scholarships or work study programs. Every day, groups of Dreamers roam the halls of Congress and crowd lawmakers’ offices.

Often in trademark blue graduation gowns, the Dreamers chant “What do we want – immigration reform. When do we want it –now!” For years, Dreamers lobbied Congress to approve legislation known as the DREAM Act that would give them legal status and a pathway to citizenship. After clearing the House, the bill fell five votes short in the Senate in 2010. Yet their advocacy pushed President Obama to issue a directive last year that allows undocumented young people to apply for provisional legal status and avoid deportation. The DREAM Act is incorporated in the Senate immigration bill. It would allow immigrant youth to apply for citizenship after five years, while their parents have to wait thirteen.

Like Christina Jimenez, most undocumented youths were brought to the U.S. as children. A founder of United We Dream, Jimenez emigrated from Ecuador to New York with her parents when she was 13. Also like Jimenez, many Dreamers were unaware of their illegal status until they applied for college.

“My advisor told you don’t have papers and your people don’t have papers so you can’t go to college,’” Jimenez said.

By selling Avon cosmetics, babysitting and other odd jobs, and with the help of parents who worked two or three jobs, Jimenez struggled to pay the tuition at City University of New York, where she majored in political science. She became an activist at 19, when immigrant youths went on a hunger strike to persuade the New York assembly to approve a law that would allow undocumented students to pay in-state tuition. “I said ‘my God, these are young people like me,’” Jimenez recalls.

She said that Dreamer affiliates voted unanimously to back the immigration bill at a convention in Kansas City in December.

They pursued comprehensive immigration reform with the same energy they focused on the DREAM Act. It may look like a children’s crusade, but Dreamers are savvy lobbyists who are adept at political theater. “Our movement was built around the idea that it should be loud and visible,” Jimenez said. “We embrace a lot of innovations and tactics that other groups may not feel as comfortable in using.”

Some of those tactics have included countless rallies in the shadow of the Capitol, a mock citizenship ceremony and Operation Bonfire, the dramatic reunification of Dreamers with their deported mothers across a fence along the border in Nogales, Texas. Lucas Codognolla, lead coordinator of Connecticut Students for a Dream, said young immigrants “definitely changed some of the dialogue” about immigration when they lobbied for the DREAM Act, which he said eased the way for Congress’ discussion of comprehensive reform. The Americanized youths evoked sympathy.

“It was putting more of a human face on the issue,” he said.

Codognolla, a 22-year-old native of Brazil, said immigrant youth pitched the DREAM Act as a way to rectify a situation “that was not our fault,” but a problem caused by their parents’ decision to come to the U.S. without legal status. Now, Codognolla said, immigrant parents are front and center.

“We are asking them not to be deported,” he said. “We need a comprehensive immigration bill that does not dehumanize anyone.”

The Senate immigration bill is hailed as historic because it is the first comprehensive bill that has moved this far in Congress in decades. The basis of the bill is the work of the so-called “Gang of Eight,” four Democrats and four Republicans in the Senate.

Rubio and New York Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer nudged the group to agree to an 844-page bill that later grew to 1,200 pages with amendments. Rubio made sure the bill was as palatable as possible to conservatives, with plenty of border protections and the requirement not a single immigrant could apply for legal status until the Department of Homeland Security puts together and launches a border control plan.

No recent immigrant would be able to apply for legal status, only those who entered the country before 2012 would be eligible. And those who are eligible could only apply for a six-year term of provisional status, which could be renewed. But those newly legalized immigrants would still not be able to receive most government benefits.

Yet the bill is not conservative enough for some lawmakers, including Texas Republican Senator Ted Cruz. A Cuban-American like Rubio, Cruz is making a name for himself in his first term in the Senate as a Tea Party hardliner who helped lead the charge against immigration reform. “If this bill were enacted, it would result in increasing illegal immigration, and it will not secure the borders,” Cruz said. He submitted a number of “poison pill” amendments aimed at sinking the bill, to no avail.

As a much touted potential candidate in the race for the White House in 2016, Rubio is on a different political trajectory and more concerned about the Republican loss of Latino voters, especially in key swing states. “We must admit there are those among us that have used rhetoric that is harsh and intolerable and inexcusable,” Rubio said in a speech at the Hispanic Leadership Network in Miami in January. He gave another emotional speech on the day of the Senate vote. “I support this reform, not just because I believe in immigrants, but because I believe in America even more,” Rubio said.

There is also a bipartisan “Group of Eight” working on immigration reform in the House, which shrunk to a group of seven with the departure of Rep. Raul Labrador (R-Idaho). He clashed with his colleagues because of his insistence newly legalized immigrants be locked out of health care programs.

While the House immigration reform group has been working on a compromise for months, it had not been made public as this issue of LATINO Magazine went to press.

Latino advocates say House Republicans will eventually vote for reform because of consequences at the ballot box of further alienating Hispanics. But there is another political reality.

Many House Republicans live in districts with few Latino voters and are more concerned with their political future than the fate of their party. “I have Republican friends that say to me ‘I’d like to help you but I can’t because I’d be primaried,’” said Grijalva.

What those GOP lawmakers fear is that a vote for reform would provoke a challenge from the right in a primary. Nevertheless, Sanchez of the National Hispanic Leadership Agenda said Latino advocates will focus their efforts on Republicans who do represent a number of Latinos and GOP House leaders. He said advocates will be “very strategic” in their mission. But he warned they will not compromise.

“Citizenship is non-negotiable,” he said. “I think we have been flexible enough.”