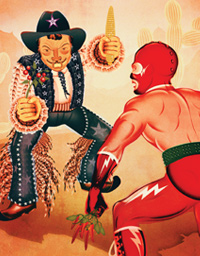

The Great Mexican Food Fight

It’s a hot Texas night, but in the blooming, light-filled atrium of Fonda San Miguel, the air feels fine, and fresh ceviche with a mango margarita cools me to the core. Tom Gilliland, the owner, is telling the story of how he helped Diana Kennedy find a publisher for her most recent work, a collection of traditional recipes entitled, Oaxaca al Gusto: An Infinite Gastronomy. I flip through the pages, stopping to admire beautiful images of native plants and countryside and women working with their hands, many of them taken by Diana herself.

I am incredibly inspired by her diligence and daring. This woman, more than thrice my age, traveled through Mexico solo for years, navigating its muddy backroads to gather recipes that Oaxacan mothers and grandmothers have passed down for decades. I’ve had the distinct pleasure of meeting Diana, who often stops by the restaurant when she’s in Austin. I was preparing for a hostessing shift one afternoon when I heard her unmistakably sharp British accent.

“Pleasure to meet you Mrs. Kennedy, I’m Katie,” I greeted her, intentionally leaving off my last name. She is known to stand vehemently behind only the purest interpretations of traditional Mexican cuisine, while my dad, Robb Walsh, is arguably the foremost authority and advocate of Tex-Mex, and openly challenges Diana’s criticisms of it. I doubt she’d hold his words against me, but I played it safe anyway. I’d heard she’s quick to dish out earfuls.

I don’t feel especially partial to either side of the “authentic Mexican food” debate, but it is a fascinating and passionate one that I’ve watched unfold second-hand for years. It’s an incredibly complex topic, one rife with history and loyalty and wildly opposing viewpoints. The way I see it, the winding path of Mexican cuisine is as much about the people as it is about the food, and the way we define it is ultimately a product of our own unique experiences in the world.

My interest in this battle over which foods have the right to be called “Mexican” was recently piqued by Gustavo Arellano, in his book Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. Gustavo hints at an interesting connection between the dismissal of modern, American-born adaptations of Mexican food and the dismissal of Mexican-Americans themselves, with this quote from Mexican-American writer Jesse Sanchez:

“Tex-Mex is important to us because it’s our bond to Mexico, even for us born in the United States. And it’s just Mexican food to us. Are we less Mexican or Mexican-American because we are Tejanos? We consider ourselves all part of the ‘Mexican food’ family and are surprised to hear when people speak of our food—or us—with disdain. The critiques sound elitist to us, and that says a lot coming from a state where we claim everything is bigger and better.”

The first time a distinction was officially drawn between food traditions from within Mexico and those that had evolved in America was when Diana published her first great work, The Cuisines of Mexico, in 1972. According to my dad, “Kennedy trashed the ‘mixed plates’ in ‘so-called Mexican restaurants’ north of the border and encouraged readers to raise their standards.” The book broke through class and caste by including the foods of Mexico’s rich and poor alike, but he points out, “while admiringly egalitarian in her attitude toward the food of Mexicans, Kennedy lambasted the food of Texas-Mexicans.”

At the time, it wasn’t just Mexican food that had become entangled in a web of Americanization and commercialization—many Americans equated Italian food with spaghetti and meatballs and pizza; Chinese food with chop-suey and chow mein. Diana took up the defense of traditional Mexican cuisine (often described as “interior Mexican”) with the encouragement of New York Times food editor and restaurant critic Craig Claiborne, described as “one of the most influential food people of all time.”

But then, celebrating traditional, international cuisines began slipping over into trashing their evolving, modern counterparts. And that’s where people like Gustavo think it goes too far. In his book, he writes:

“...[a succession of white authors and acolytes] introduced a fraudulent concept to the question of Mexican cuisine in this country: the idea that the food they documented was ‘authentic,’ while the dishes offered at your neighborhood taco stand or sit-down restaurant were pretenders to be shunned.”

Gustavo lumps Oklahoma-born and Chicago-based Rick Bayless, chef and owner of Frontera Grill and author of Authentic Mexican and Mexico: One Plate at a Time, into that succession. While Rick’s characterizations of Mexican-American food can be unflattering and his dedication to interior Mexican is clear, he isn’t as black-and-white or zealous about it as Diana. His experience is a different one.

In the introduction to Authentic Mexican, Rick tells the story of growing up on “El Charrito down on Paseo with its oozy cheese-and-onion enchiladas smothered with that delicious chile gravy.” Rick upholds the line between Mexican food from Mexico and that from the U.S., but doesn’t write off the regional cuisines of Texas, New Mexico, and California. He writes:

“...after a number of years shuffling between the two cultures, I have come to a simple answer: There have developed two independent systems of Mexican cooking. The first is from Mexico, and (with all due respect to what most of us eat and enjoy in this country) it is the substantial, wide-ranging cuisine that should be allowed its unadulterated, honest name: Mexican. The second system is the Mexican-American one, and, in its many regional varieties, can be just as delicious.”

That sounds pretty diplomatic to me, although there’s still this problematic idea that Mexican and Mexican-American food are “independent” of one another, rather than part of the same continuum. The Mexican food traditions Rick and Diana love so well are a blend of ancient indigenous and European influences, which then went on to blend with the ingredients and experiences Mexicans found in America.

Rick laments the image of Mexican food created by “Chi Chi’s or El Torito’s or whatever the regional chain restaurant is called,” saying that it “seems...to have become a near-laughable caricature created by groups of financially savvy businessmen-cum-restaurateurs who saw the profits in beans and rice and margaritas.”

He’s partially right, but the story isn’t so simple. In fact, El Torito, a popular 1980s “patio dining” chain that served as a precursor to today’s Taco Cabana, was founded by Larry Cano, an American-born Mexican who faced a difficult upbringing rife with segregation and the struggle. El Torito was his own creation, his self-made success story, one borne of his unique experience. Gustavo quotes him as saying,

“I always had mole and chile colorado on my menus. They never sold in the early days, but it was my cuisine. We had to have them on because that authenticity distinguished us from everyone else. I couldn’t conceive of preformed taco shells. It just wasn’t my cultural experience. Sure, the food had to appeal to a larger audience, but not down to the level of others.”

Cultural experience, in my eyes, is the driving force behind this entire impassioned throw-down. The experience of a British woman or American man studying traditional Mexican foodways is worlds away from the experience of a Mexican man or woman giving those foodways new form in America. As time goes on, cultures morph and change. Peoples and their ways of life naturally begin to blend together. My dad posits that this melding and mixing of cultures is the underlying cause for debate about Mexican food. In Taco USA, he is quoted as saying:

“The people who are opposed to Tex-Mex now are opposed to it for some reason of purity. It’s mongrelized, it’s bastardized, right? The people who are upset with with Tex-Mex are upset with miscegenation. To the extent that we’re comfortable with interethnic marriage, we’re comfortable with mixed ethnic cuisine.”

It’s hard to make these broad-stroke generalizations of anyone on any side, though. Chef Alma Alcocer-Thomas, who also worked at Fonda San Miguel and now has her own Mexican restaurant, said that while she loves doing modern and inventive things with Mexican cuisine, she draws a line between Mexican and Asian.

“My view is my own experience,” she told me. “I was born and raised in Mexico City, and to me a quesadilla with brie is just as Mexican as one made with Mennonite cheese. But unlike a lot of younger chefs, I have a limit to what I’ll do to Mexican food. As much as I love Japanese and Korean food, I think that’s kind of where I personally draw the line.”

While she admits that her limits are influenced by “Diana screaming bloody murder in my ear,” they also have to do with her upbringing in Mexico City. “Sushi has been incredibly popular in Mexico for years and years, and they do a lot of things to sushi. I remember the first time I saw a deep fried sushi roll, it just broke my heart,” she recalls.

Alma isn’t opposed to the melding of cultures altogether, but her own cultural experiences have informed where she will and won’t go as a chef. She divulges that she’s never tasted a Korean taco—a combination of warm corn tortillas, beef bulgogi, chopped onion, cilantro, and kimchi, which signals a new wave of cultural experience and culinary hybridization. Today, Mexican food has wooed even those of other foreign and hyphenated backgrounds in America. Gustavo quotes Larry Cano as saying, “The fusion of Mexican food with others is the next step.”

To me, the evolution of Mexican cuisine in and out of Mexico, and the natural process of blending cultures and ingredients and ideas, is indicative of a larger trend in the modern world—one in which invisible borders drawn by history and winners of conquest are beginning to fade, or at least to take on new meaning. In its many forms, Mexican food has taken root not only in America but also Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. Can’t our embrace of it, and the people making it, be as wide in its reach?

Gustavo thinks so. “Maybe eventually,” he says. “I’m an optimist. It’s all a process, and it doesn’t happen overnight. But it will happen.”