There’s the Hope diamond, moon rocks, the Spirit of St. Louis, and a dizzying array of artifacts and collections that chronicle American history, politics and culture.The world’s largest research complex, the Smithsonian Institution runs 19 museums and galleries and the National Zoo, facilities that attract about 30 million visitors each year.

But Latinos have long complained the Smithsonian does not adequately showcase the contributions of Hispanics to the development of this country. A determined group says nothing short of a National Museum of the American Latino will make up for years of ignoring our history and culture.

Yet the effort is stalled by lack of support in a very polarized Congress and little interest from the Smithsonian itself. Not a single dime has been raised to build the museum, estimated to cost at least $650 million. But lawmakers and influential Latinos continue to push for the idea.

Among those in support are Rep. Xavier Becerra (D-Calif.) and Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.) who have sponsored legislation that would establish the museum.

“Too many times the culture of people of Latino decent has gone missing,” Becerra said. “It’s a real void and it’s been acknowledged as such.”

A 15-member task force appointed by the Smithsonian itself issued a report in 1994 called “Willful Neglect,” that found the institution has virtually ignored Hispanic contributions to American art, culture and science and “displays a pattern of willful neglect ,” toward millions of Latinos living in the U.S.

The Smithsonian has since taken steps to make amends by stepping up its temporary exhibits of Latino culture and by establishing the Smithsonian Latino Center to coordinate those exhibits and reach out to the community. But museum advocates like Becerra say it’s not enough. They say Latino culture belongs on display on Washington D.C.’s monument mall, which is ringed by museums, including the National Museum of the American Indian and a new one under construction that will be dedicated to African American culture and history.

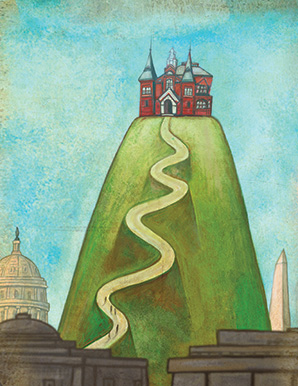

Becerra’s legislation would require the planning, designing and construction of a museum in the Arts and Industries Building, the second oldest Smithsonian museum on the mall. Built in 1879, it’s an impressive Victorian pile of stone that’s now empty and in a state of disrepair.The legislation would also require the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution to consider plans for a Latino museum drawn up by the Commission to Study the Potential Creation of a National Museum of the American Latino.

The commission was established by legislation that was also sponsored by Becerra in 2003. It took five years to become law. It created a 23-member panel whose members were appointed by President Obama and the leadership of the House and Senate. The commission completed its report in May of 2011, which determined:

“American Latinos are inextricably woven into the fabric of the United States and have contributed enormously to the development of our great nation for the benefit of all Americans, and to ensure our country’s future vitality, there is a compelling need to better tell this story. Through an exhaustive process, the Commission has determined that a national museum focused on American Latino history, art, and culture is not only viable but essential to America’s interests.”

But the commission said that half the money to create a museum should be raised by private donors and taxpayer money should not be involved in its design and construction for the first six years. The report also said it would take a decade to establish the museum. That timeline is now considered overly optimistic.

Becerra’s pending legislation would be the next step in the process, requiring Congress’ to give final approval for the museum. But a similar bill died in the last Congress. Critics say the proposal encourages cultural isolationism, would aggravate crowding on the mall and cost too much at a time of deep concerns over the federal budget.

Becerra’s latest bill has only 11 co-sponsors and is languishing in Republican–dominated committees. Menendez’s companion legislation in the Democrat-controlled Senate isn’t having any better luck. Nevertheless, Becerra, a Mexican-American whose father worked construction and other blue-collar jobs, said he’s not daunted, especially after he considers how his father struggled.

“It’s hard for me not to be optimistic that we’re going to get a museum,” he said. “Difficult is working up and going home to hungry kids. Difficult is getting up at 4:00 a.m. and working all day and having nothing. It’s going to take some time but it’s going to get done.”

Becerra said his campaign for a museum is motivated in part by his frustration of the general lack knowledge outside the Hispanic community about Latinos.“I bet if you would ask people to name the first settlement in America, very few people would say St. Augustine,” Becerra said. “Even something simple, like the fact Latinos fought for American independence, is unknown.” History, Becerra said, helps shape policy. “As members of Congress, we make decisions based on history.”

But for Becerra, the absence of Latinos in popular culture is as damaging, or more, than a lack of knowledge about the role Latinos played in American history. He cites a 1960 movie, From Hell to Eternity, about a Marine hero in World War II’s Battle of Saipan, Guy Gabaldon, who was actually Chicano but played by non-Hispanic Jeffrey Hunter in the film.

“Folks should understand we have been shut out of American life,” Becerra said.

Some worry that political, and financial support for the Latino museum may be diluted by a competing push to create a National Museum of the American People that would focus on the history of immigration into the United States. In 2011, legislation calling for a commission to study the proposal was introduced in Congress to honor “every American ethnic and cultural group coming to this land and nation from every corner of the world, from the first people through today.”

Becerra also supports plans to build what’s being called “the immigration museum,” which some say could compete for scarce funding with the Latino museum. But Becerra says that’s not a priority right now. “We will concentrate on that in the future. The [National Museum of the American Latino] consumes a lot of my energy right now. I’ll take a look at the other effort later on, right now I’m focused on this effort.”

Museum boosters have formed a group called Friends of the National Museum of the American Latino, which was established not only to promote the museum but to eventually raise hundreds of millions of dollars to get it off the ground. According to its website at AmericanLatinoMuseum.org, board members include corporate heavyweights such as Susan Gonzales of Facebook, Fernando Laguarda of Time Warner Cable, and Lillian Rodriguez-Lopez of Coca-Cola. The Friends have also enlisted the help of celebrities like Eva Longoria. “We absolutely need a Latino American museum on the national mall,” Longoria said in a video produced last summer to help lobby for the effort. “Latinos are part of the fabric that makes up this beautiful country of ours and it’s important for the younger generations to understand that part of history.”

Estuardo Rodriguez, a lobbyist with the Raben Group in Washington, DC, is the executive director of Friends. He’s confident Becerra’s bill will move forward, if not by the end of the year, then in the second session of the 113th Congress, which begins in January. He said Becerra has clout because he has the fourth-ranking job in the Democratic House leadership, that of chairman of the Democratic caucus.“He’s got a direct line to the congressional calendar,” Rodriguez said. Still, the GOP controls the House floor schedule, and the committees that must first vote out Becerra’s bill.

Rodriguez, a Washington D.C. native whose family comes from Peru., said there’s real pressure to establish the museum soon before anyone else lays claim to the Arts and Industry Building. A ban was imposed on building any new museums on the monument mall after Congress approved construction of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2003. So, if the National Museum of the American Latino will sit alongside the other Smithsonian museums on the mall, it must move into the now empty Arts and Industry Building, which is undergoing emergency repairs to keep it from crumbling.

Meanwhile, groundbreaking on the African American museum began last year and huge construction cranes loom over its 5-acre site between the Washington Monument and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The museum is expected to open in 2015, a dozen years after Congress gave its approval. There are differences and parallels between the efforts to create a museum to honor the nation’s black history and one to honor Latino history---besides the fact that the National Museum of African American History and Culture will housed in a new facility especially designed for it, the last to be built on the monument mall.

Lonnie Bunch, director of the African American museum, said its purpose is “reconciliation and healing.” He also said plans to build the museum rushed ahead of the acquisition of a single item to display. “Traditionally, when you build a museum, you already have the stuff, “Bunch said. “Well, we didn’t.” But donations of historic artifacts are coming in, Bunch said, many from people’s basements and attics.

The National Museum of the American Latino may be easier to fill.

“There are museums of Latino history already all over the country that can send us [exhibits],“ Rodriguez said. “And the Smithsonian has several hundred pieces which are in storage because they don’t have space to display them. The collections are out there.”

It was also easier politically to win support on Capitol Hill for approval of the African American museum and Congress was less resistant to help pay for it. In addition, private donors have given millions of dollars to create the African American museum. Oprah Winfrey has donated $13 million alone. But the only fundraising related to the Latino museum is the money Friends has raised to fund its operations, which in 2013 included events in Miami, Houston, New York and Las Vegas. There is also a staff of six, all listed on the website as employees of the Raben Group. Rodriguez said annual costs are between between $150,000 and $200,000.

The Friends plan to create a social media database that can tap up to one million small donors when it’s time to raise money to build the museum. Rodriguez said he has 350,000 people in the database now and his focus is on grassroots support. “One dollar here, five dollars there, it will all add up,” Rodriguez said. “You can’t point to one person and say ‘that’s our Oprah Winfrey,’ but many of those in the [Latino] community have an extensive network.”

For some Latinos, the money could be better channeled into pressing for immigration reform or better education. But to Ingrid Duran, co-founder of D & P Creative Strategies, a Latina-owned lobbying firm, the Latino museum is “imperative.”

“I absolutely think it’s worth the effort,” she said. “When you look at museums and monuments on the mall, you see the history of the United States, void that of the Latinos.People tend to think there are other priorities money should be spent on. But capturing the history and culture of the Latino community is important.”

Duran also said there’s a good reason bills that would establish the museum aren’t making much headway.“Given the legislative priorities right now, the budget, tax reform and immigration, you have a lot of issues that are critical, you don’t want to waste your political capital until the timing is right,” she said. “Becerra will know when the timing is right.”

Richard Kurin, the Smithsonian’s Undersecretary for History, Art, and Culture, oversees the Smithsonian Latino Center that was established after the devastating “Willful Neglect” report in 1994. “The idea was that the Smithsonian had to do a better job representing the Latino experience,” he said.

The Center ramped up its creation of temporary exhibits of Latino-related themes. Kurin is proud that the Smithsonian Folkways production of the East Los Angeles group Quetzal won a 2012 Grammy for “best alternative rock album.” He cites notable exhibits sponsored by the Latino center that have included a retrospective of the work of Cuban songstress Celia Cruz and “Bittersweet Harvest,” which focused on the Bracero movement in the United States. “Those people had tough lives,” said Kurin about the Braceros, Mexican farmworkers imported to the United States during World War II and other times when farm laborers were scarce.

Kurin said the Center has also sponsored exhibits of lowriders, customized cars originated by Mexican-Americans in Southern California, of Latinos in the U.S. military and The Latino Presence in American Art. “And we always include Latinos in our Folklife Festivals,” he said. But these efforts have done nothing to silence calls over the years for a permanent Latino museum in the nation’s capital.

The Smithsonian must be neutral in the debate since it receives most of its money from Congress. “They don’t take a position, but they will do what Congress asks them to do,” Becerra said. Kurin said the Smithsonian cannot lobby for the creation of the Latino museum, “but if Congress passes the law, we would welcome the museum into the family.” He said, however, Latino museum supporters should have patience. “Look at the African American museum, look at the American Indian museum, it takes generations,” he said. “You don’t get to build a museum very often.”

Kurin said it took 100 years to establish the Smithsonian’s American History Museum. He also said plans for the Air and Space Museum began in the 1920s and 1930s, but the facility, perhaps the Smithsonian’s most popular, did not open until 1976. There was a push by former slaves for an African American museum right after the Civil War. But President Bush did not sign legislation creating the museum until 2003, Kurin said. “These things take time.”

By Ana Radelat