Last September, the world was shocked when 43 students from a rural teachers’ college in Mexico disappeared. The missing were said to have been incinerated at a dump by a drug gang working with local police. Since December, only two of the students have been identified, and in both cases the families disbelieve the official story. Herrera gives voice to the victims of this horrific tragedy in his poem “Ayotzinapa,” writing “they dismembered us in trash bags they threw us into the/ river yet we continue yet we march from here from the bowels of Mexico.” The chorus of the disappeared intones: “we are not disposable.”

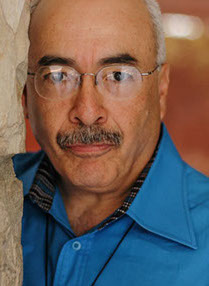

The 66-year-old Fresno, California-based poet does not shy away from the ugly thread of police-related murder that seems to have run through the whole of 2015. In “Almost Livin’ Almost Dyin” Herrera arranges victims of cop violence like Eric Garner and Michael Brown in the same urban lament with slain peace officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos.

Although the book rings with a necrotic vibe, not all the focus is on violent death. Herrera’s collection hums in dark, brassy vibration with tribute and respect. There is actually quite a lot of eulogy in Notes on the Assemblage, a lot of better-late-than-never praise for writers like Wanda Coleman and Philip Levine. The targets for his tributes are  across the board. Herrera’s voice goes out to sick relatives, dead friends, art as well as detention centers; he extols Kant and Kenji Goto, and does not forget Trayvon Martin.

across the board. Herrera’s voice goes out to sick relatives, dead friends, art as well as detention centers; he extols Kant and Kenji Goto, and does not forget Trayvon Martin.

Linking themes as disparate as the L.A. Riots and avant-garde Italian cinema, there is a tone of casual esotericism in his verse. Herrera’s lines often ape E.E. Cummings, and more or less assume the reader’s familiarity with the Dadaist Hugo Ball. However obscure his arcana might be, the poet’s voice remains gracious and non-exclusive.

If there is a brotherhood out there, he seems to say, it is forged around the pangs of threat that compel people to unite and to incite. Herrera’s work, sticking to the strictures of sound and symbol, offers ample example that socially conscious literature might work best as it approaches song.